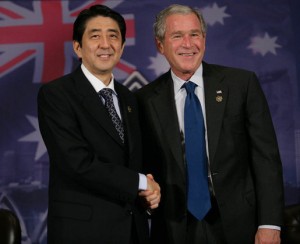

Shinzo Abe became prime minister of Japan in December, more than six years after he first took the job, succeeding long-serving Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in September 2006. In the U.S. press especially, Abe is often termed a “nationalist” or “hawk” for supporting expanded military activities and a potential revision of the Japanese constitution.

Crystal Pryor, a Japan Studies Visiting Fellow at the East-West Center and a Ph.D. student in political science at University of Washington (and my former office-mate), released a very useful brief pushing back on U.S. coverage of the new prime minister in Japan.

To keep things in perspective, it’s worth reviewing the actual text of Article 9 of the constitution, which I will render verbatim but in outline form. And it’s worth remembering that advocates of change are pushing for revision, not repeal.

Article 9.

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce

• war as a sovereign right of the nation and

• the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph,

• land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained.

• The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Pryor writes:

As the Japanese constitution is currently interpreted, Japan cannot take military action if an ally, the United States, is attacked because Japan does not have the constitutional authority to engage in collective self-defense. Even activities such as sending the Japanese Self-Defense Forces on UN PKOs in the 1990s or on refueling missions in the Indian Ocean after 9/11 in support of the US-led operation in Afghanistan faced major domestic hurdles. Japanese politicians calling for Japan to shoulder its half of the security alliance or to send troops on PKO missions can hardly be considered “hawkish” by American standards.

On the constitutional question, one can immediately see that revision of Article 9 need not completely erase restrictions on warmaking in order to carve out the right for Japan to “pull its weight” in the U.S.–Japan alliance or in U.N. peacekeeping operations.

Pryor also argues that Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) did not beat the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) because of its “nationalist” character. On this point, few would disagree: Analysts almost universally characterized the LDP electoral victory as a rebuke of the flagging DPJ leadership and economic policies. Pryor also notes that low youth voter turnout undermined the DPJ.

So what of the emphasis on nationalism and hawkishness? Five years ago, the connection between Abe’s name and the word “nationalist” was already a point of discussion. In the midst of a conversation between the blogger Ampontan (who recently passed away, and whose voice is missed despite differences of opinion) and Tobias Harris at Observing Japan, I compared Abe’s reputed nationalism to that of Junichiro Koizumi, whose repeated visits to the Yasukuni Shrine drew loud opposition from leaders in China and South Korea:

As we know, Koizumi spent much more time and international political capital than Abe has in paying tribute to Japan’s late 19th—early 20th century nationalism. But Abe has spent more energy on a more contemporary and more instrumental form of nationalism, the revision of Article 9. The rhetoric behind constitutional revision—especially among the people usually called “nationalists”—often invokes the desire for Japan to become a “normal state.”

Indeed, for all the fear about a potential Japanese remilitarization, Abe has not been a particularly extreme voice in Japan. Though it may not repair perceptions of his orientation among others in the region, Abe is not the biggest “hawk” in the Japanese political sphere.

As Pryor notes, some real hawkishness comes with the emergence of a “third force” in Japanese party politics. “[Shintaro] Ishihara, who gave up his position as governor of Tokyo for this election, is a hawk even by American standards. Most recently, he played a central role in reigniting the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute by declaring that Tokyo would purchase and develop the islands. Ishihara has also called for Japan to revise its current constitution and develop nuclear weapons.” It was Ishihara’s provocation that led the Japanese national government to take legal control of the islands. Though that move was blasted by many in China, the islands likely would be even more of a sticking point if Ishihara controlled them.

So Japan’s political stage is, unsurprisingly, more complicated than portrayals in U.S. news stories. But the perception of an agressive, nationalist, or unrepentant Japan is real among some in China. Every day in Beijing, I still see bumper stickers declaring “钓鱼岛 中国的” (“The Diaoyu Islands are China’s”)—or, more aggressively, “打倒小日本!” (roughly, “Take Down Little Japan!”). The Wall Street Journal writes from Tokyo that “while [Abe] seeks a more assertive Japanese presence in the region, he isn’t about to provoke China or risk worsening already strained relations between Tokyo and Beijing.” I’m just not sure Chinese media and official voices, let alone those mobilized in the 2012 anti-Japan protests, are on the same page.

Leave a Reply