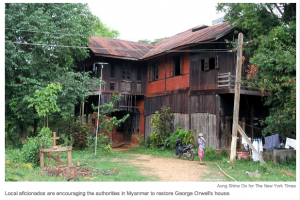

At the recommendation of a friend in Beijing, I’ve been reading George Orwell’s Burmese Days. Coincidentally, Jane Perlez of The New York Times recently traveled to the real town Orwell was stationed in that inspires the novel’s setting. She calls the book “a scathing portrait of the imperious attitudes of the British, from this former colonial outpost on the banks of the mighty Irrawaddy River.” Some of those imperious attitudes sound strikingly similar to, if far more strident than, the complaints and judgments of some expatriates in Beijing.

One of the central tensions of the novel, which I haven’t finished (and so neither did I read the end of Perlez’s story, where she got back to the plot), is that one Englishman, named Flory, is unusually sympathetic to the Burmese, while the rest of the European population is savagely racist and dismissive. This passage pretty much sums it up.

There was an uneasiness between them, ill-defined and yet often verging upon quarrels. When two people, one of whom has lived long in the country while the other is a newcomer, are thrown together, it is inevitable that the first should act as cicerone to the second. Elizabeth, during these days, was making her first acquaintance with Burma; it was Flory, naturally, who acted as her interpreter, explaining this, commenting upon that. And the things he said, or the way he said them, provoked in her a vague yet deep disagreement. For she perceived that Flory, when he spoke of the ‘natives’, spoke nearly always in favour of them. He was forever praising Burmese customs and the Burmese character; he even went so far as to contrast them favourably with the English. It disquieted her. After all, natives were natives—interesting, no doubt, but finally only a ‘subject’ people, an inferior people with black faces. His attitude was a little too tolerant. Nor had he grasped, yet, in what way he was antagonising her. He so wanted her to love Burma as he loved it, not to look at it with the dull, incurious eyes of a memsahib! He had forgotten that most people can be at ease in a foreign country only when they are disparaging the inhabitants.

The life of an American or European expatriate in Beijing is categorically different. We are not colonial authorities, nor is urban China so terribly exotic compared to other global cities. But the tension is real between people who seek only to complain and disparage, and those who seek to understand and engage. That tension can frequently be recognized even within individuals. What today’s reality in Beijing shares with Orwell’s account is a language of separation.

In this second passage, Orwell laments the assault on a European’s own dignity that occurs when he or she is bound by colonial social norms. In the plot, Flory had decided to betray a non-European friend, because to stand with him would have led to great problems for him among the Europeans.

It is a stifling, stultifying world in which to live. It is a world in which every word and every thought is censored. In England it is hard even to imagine such an atmosphere. Everyone is free in England; we sell our souls in public and buy them back in private, among our friends. But even friendship can hardly exist when every white man is a cog in the wheels of despotism. Free speech is unthinkable. All other kinds of freedom are permitted. You are free to be a drunkard, an idler, a coward, a backbiter, a fornicator; but you are not free to think for yourself. Your opinion on every subject of any conceivable importance is dictated for you by the pukka sahibs‘ [a term for Europeans as a ruling class in the British empire] code.

Again, things are very different. But is there a degree of groupthink among China watchers? Are there times when taking the side of the Chinese people or government in a political argument is a kind of taboo? I think so.

Back to the novel.

Leave a Reply