Pivot. “I personally don’t like the term,” said Jeffrey Bader, former senior director for East Asia of the U.S. National Security Council. It was an “unfortunate word” selected by staff seeking a positive press response to President Barack Obama’s trip to Asia in 2011, he said at Beijing’s Tsinghua University on Nov. 29, 2012. Each time the president goes to Asia, he said, the story is always about China, and there are two options: Either the United States came as a supplicant and is in decline, or it put China on its heels. Both stories are wrong, Bader argues, but the word “pivot” was selected to push for the second story in the U.S. press.

The word “pivot” swiftly became “rebalance” in U.S. government statements. To some, it had implied a turn away from other regions, not a reassuring message for those seeking continued support in the Middle East. Some also thought it implied that the United States would shift its interventionist tactics from the Middle East to the Asia Pacific region. “Rebalance” was rolled out with more nuance, emphasizing at times that it implied only minor increases in the Pacific, instead emphasizing drawdowns elsewhere. Then, the question of whether the “pivot” or “rebalance” had failed as a strategy soared to the top of the discussion after Obama was reelected. In Secretary of State John Kerry’s confirmation hearings, he implied limited support for a shift of resources: “I’m not convinced that increased military ramp-up is critical yet. I’m not convinced of that. That’s something I’d want to look at very carefully when and if you folks confirm me and I can get in there and sort of dig into this a little deeper.”

With the pivot/rebalance downgraded as a strong-on-China rhetoric, and the deep need for greater engagement with China, what was left to keep the press on the “China on its heels” narrative? Consider cybersecurity. President Obama began a rollout with the State of the Union this year. Without naming China, he made “enemies [who] are also seeking the ability to sabotage our power grid, our financial institutions, and our air trafic control systems” the China policy point. The day before, someone had leaked to the Washington Post a classified National Intelligence Estimate naming China as the most aggressive cybersecurity threat.

In the coming days, the private online security firm Mandiant released a report that allegedly detailed Chinese military involvement in spying on U.S. businesses. A “senior defense official” told The New York Times, “In the cold war, we were focused every day on the nuclear command centers around Moscow. … Today it’s fair to say that we worry as much about the computer servers in Shanghai.” Then the White House released its “Strategy to Mitigate the Theft of U.S. Trade Secrets,” which does not name China in the body text but features it in six of the seven theft examples in sidebars.

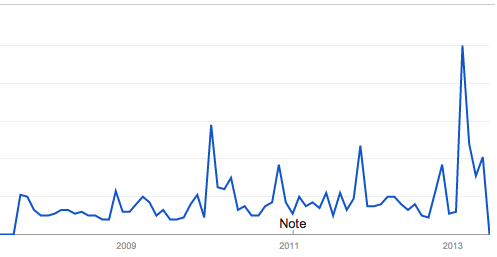

This drumbeat has continued through February and March and up to today. National Security Advisor Thomas Donilon said in a speech in March that “intellectual property and trade secrets” had “moved to the forefront of our agenda.” Since then, cybersecurity, often with some degree of conflation between national security threats and threats to private intellectual property, has moved to the top of the U.S. media agenda on China, along with North Korea. In the White House background briefing on the upcoming summit between Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping, the briefers didn’t have to bring up cybersecurity. The first question and half of all questions mentioned the topic (including the meta-question “how do you keep this summit from being a cyber summit?”). Admittedly impressionistic data from Google Trends shows U.S. searches for “China” and “cyber” peaking in February.

Now, the White House is in the midst of a significant surge in China diplomacy with considerable attention to the future. The Obama-Xi “shirt-sleeves summit” near Palm Springs, Calif., to take place Friday and Saturday was preceded by, among other efforts:

- Vice President Joe Biden’s trip to China in August 2011.

- Xi’s trip to the United States as vice president and heir-apparent, with Biden as his host and an Oval Office meeting with Obama in February 2012.

- Secretary of Treasury Jack Lew’s trip to China in March 2013.

- Secretary of State John Kerry’s trip to China in April 2013.

- Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey’s trip to China in April 2013.

- The April announcement of the 2013 round of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue to be held in Washington July 8–12, 2013.

- National Security Advisor Thomas Donilon’s trip to China in May 2013.

It’s possible to view the dogged focus on cybersecurity in the media and in government statements as misplaced. After all, it is unclear what if any effect on actual operations the “naming and shaming” process is having, and we will have to wait and see what further measures the U.S. government might take. Meanwhile, other issues such as energy and climate cooperation, maintaining stability around North Korea, and military-to-military relations are also pressing. Perhaps most of all, say (almost) all the comments out there, Obama and Xi have the opportunity to open a new chapter of U.S.–China relations through high-level dialogue and building a “new kind of great power relations” (Chinese wording) or a “new model of relations between an existing power and an emerging one” (U.S. version).

These cooperative notes, however, could trigger the media narrative Bader said the administration dreads: the United States as declining supplicant. Instead, the administration gets to claim they will raise cybersecurity in this and other interactions. They have high-level working groups in progress or planned for cybersecurity (a challenge) and climate change (an opportunity and a challenge). And needless to say, there is the benefit of getting a very serious issue for U.S. businesses and the U.S. national security community on the table in a way the Chinese government cannot entirely ignore.

Leave a Reply