Readers of English-language news on China have likely noticed a surge in references to netizens, microblogs, and a specific microblogging service called Sina Weibo. Angel Hsu noted this was increasing, and I thought I’d check to see how much.

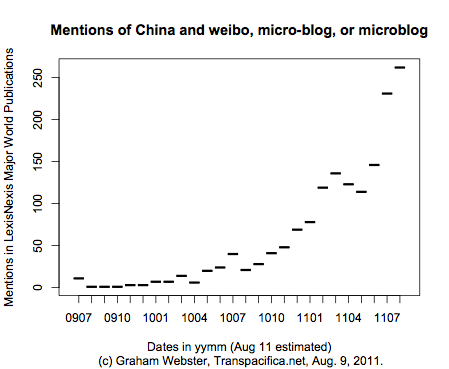

For a really rough measure of how much foreign reporters are depending on Chinese microblogs to cover public sentiment, I searched LexisNexis’s “Major World Publications” database for mentions of China along with any one of the words “weibo,” “microblog,” or “micro-blog.” (Weibo, in addition to being Sina’s brand, literally means “micro blog.”)

This measure is horribly imperfect. To begin with, some stories are double-counted, and there’s no reason to assume Nexis is representative of foreign media. Moreover, some of these mentions are stories about Sina Weibo itself, not quoting its users. I wrote one such article for Talking Points Memo.

The trend, however, seems clear. After the first mentions in mid-2009, when Sina Weibo launched, Nexis shows few mentions until a surge beginning in late 2010. In the last few months, the trend is upward.*

See for yourself:

*Note: I counted 76 stories so far in August 2011, which leads to an estimate of 262.

*Note: I counted 76 stories so far in August 2011, which leads to an estimate of 262.

If you want the data yourself, for what it’s worth, you can find a CSV file here. Please respect the Creative Commons license under which this site is published.

Update: Chinese translation / 译言网翻译

Leave a Reply