For centuries, and especially since the mid-19th century, entrepôts have been important sites of communication—both information and goods—between China and the outside world. Now, many of the same cities are sites of the grand digital switches that connect China to the global internet.

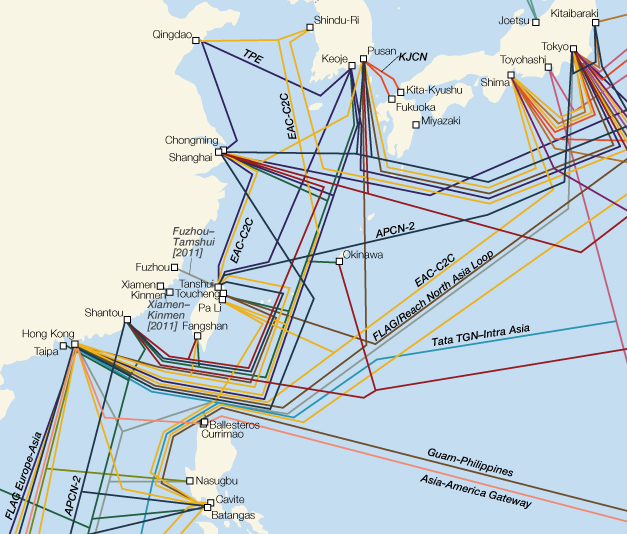

I’ve noted before the interesting work of TeleGeography, a firm that produces maps and other information on telecommunications infrastructure. This year, their world undersea cables map has been released as a huge JPEG image, and it shows us something about China’s communications with the outside world.

Shanghai, Hong Kong, Qingdao and Shantou. And soon, Fuzhou. These are the connection points for the People’s Republic of China, and they were all treaty ports, where foreign areas of control existed and international trade grew.

The analogy to the treaty ports has been suggested by several writers. One, Han-Teng Liao, noted Aihwa Ong’s notion of variegated sovereignty and proposes the idea of “special speech zones.” These “SSZs” are cites of informational interchange. The difference is that the SSZs are not geographically bounded; rather, they reside in online spaces where relatively free speech is possible.

As Ella Chou recently noted (in her very interesting contribution on cybersecurity), China only has a few ports between China and the outside internet—nine at last report in 2008, she writes. These choke points, one speculates, could allow for a government-directed shut-down of most international online communication.

This leverage points out a key difference with the entrepôts and treaty ports of the 19th century: Back then, the foreign influence was inscribed in physical space, with exclusive areas of control and entrenched foreign populations. Sure, expatriates are numerous in many Chinese cities today, but they do not live in autonomous zones. The potential for increased control in a crisis seems clear here.

That’s all from me. But look at that map.

Leave a Reply